Capitalism is being forcibly subjected to some new dynamics as a result of the Covid-19 crisis. Out of necessity, “state-directed capitalism” is rising – with governments and central banks applying pressure on private enterprises to lend and stimulate the economy.

Whilst the short term outcome of this new paradigm is – hopefully – to weather the severe economic and business impact of the virus, the longer term consequences are harder to read. We asked 50 leading City figures – senior bankers, fund managers, CEOs, Chairmen and NEDs – their views on what post-Covid capitalism might look like and received a fascinating response.

What are the implications of these findings for companies – both City firms and PLCs? Our five key take-outs are:

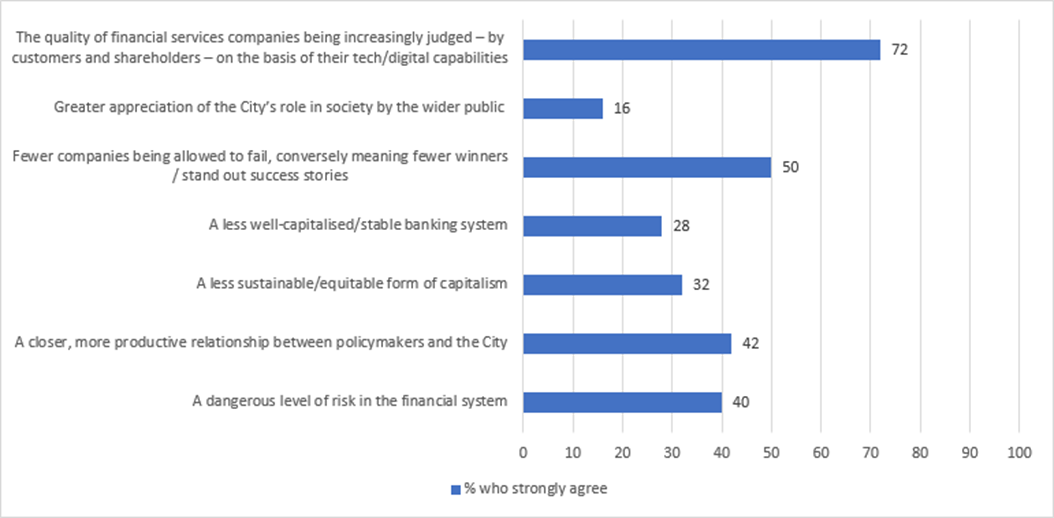

- Technology – both its “defensive” importance in operational resilience and as a positive differentiator of a company’s offering – should be prominent in any corporate narrative or equity story. Companies should identify their tech proof-points which give them a genuinely leading position or a competitive advantage, as opposed to tech operations which are now considered basic corporate hygiene. As one respondent put it: “The ability to fulfil client demand through multiple channels and to optimise products and services will be the new normal. Shareholders will evaluate investment viability through such execution and strategic aspiration.”

- Articulating a clear, long term strategy becomes increasingly important. Half of respondents said they strongly agree that state support, in the form of QE, fiscal stimulus and aggressive lending will mean fewer stand-out success stories. This presents both a threat and an opportunity. Differentiation may be more challenging but those that can achieve it – by demonstrating that they are delivering against a long term plan and are set up for sustainable success – will reap rewards in terms of growth and valuation.

- The level of risk in the system has been brought into sharp relief, with four in ten respondents voicing that they foresee “a dangerous level of risk” in the financial system in the aftermath of the Covid crisis. For banks and asset managers, this will place more of an onus on communicating the specifics of their risk management – their processes, due diligence and methods of analysis. For listed companies, balance sheet strength – and how this is reflected in capex, dividend policies etc – becomes an even greater focus.

- Lobbying efforts may receive a more sympathetic hearing. 42% of respondents suggested that the relationship between the City and the policymaking community may improve post-crisis. Firms with a clear, robust and well-researched position on where and how policy should evolve may find themselves well-placed to influence change.

- Whilst the City’s efforts – both directly in terms of supporting customers and clients and indirectly through their broader charitable/societal initiatives – have received plaudits in some quarters, it is unlikely that the “brand” of the financial sector will materially change in the eyes of society. Trust in financial services is beginning to return, incrementally and over time; according to the Edelman Trust Barometer (2020), trust has improved 12 percentage points over the last eight years – the most of any sector – yet is still ranked at the bottom of the list of industries by its trust score. A vast amount of work is still required to rebuild the reputational damage that occurred during the Financial Crisis more than a decade ago.